The Psychological Roots of Trump's Appeal

When people believe fakeness is increasingly around them, they seek "charisma" as a signal for authenticity

Few things illustrate the two opposing types of politicians—and their contrasting approaches to politics—better than these short videos featuring their representatives.

Here’s the first one:

Gad Saad comments: “There are no words, no sentiments, no non-verbal cues, no telepathic communications that can capture the extent to which this individual is grotesque.”

Given the popularity of his comment, it seems many people share his sentiment.

Here is the second type:

To a lot of people, the thing that comes to mind when listening to the first type of politician embodied by the likes of Justin Trudeau is the word “fake”.

The first type says all the (politically) correct words: He is polite, agreeable, respectful, and a people-pleaser. But at the same time, there is an impression he lacks “authenticity”, “character,” or what we would call “charisma.”

Someone who has charisma or a character stands on opposite grounds to someone who is a poseur, an NPC, or a normie, to use some of the terms popular in online discourse.

Indeed, the derogatory nature of terms like “NPC” and “normie” can be understood as a reaction to some of the observed social trends. For example, a recent study has found:

a notable decline in people’s motivation to stand out or be unique over the past two decades. Researchers analyzed data from over one million people between 2000 and 2020, measuring various aspects of uniqueness, including willingness to defend beliefs, adherence to rules, and concern over others’ reactions. Results revealed declines across all three areas.

There is a reason people talk so much about the impostor syndrome.

On the other hand, the second type of politician, embodied by the likes of Donald Trump, is more of a reaction to the first type.

This may be a “reaction” in an almost aesthetic sense, where people get tired of the first type once the political scene becomes saturated with it.

But the demand for this “reactive” type of politician may also be the result of declining public trust: when people believe fakeness is increasingly around them, they may seek "charisma" or "character," as a cue for authenticity.

Consider why people say phrases like “imperfections create character”. Perfection is hard to achieve naturally so anything resembling perfection is more likely to be fake and artificial. Imperfections are what make fictional characters more believable, relatable, and lovable.

The heuristic people might rely on here is that someone who is imperfect likely invests less effort in faking, and is, therefore, more trustworthy.

Acting spontaneously or saying whatever pops into your mind—or at least its appearance—can indicate whether someone is trying to appear to be something they are not, meaning observers can use it to gauge how "fake" a person is.

This is why I think Ezra Klein is on to something when describing Trump’s most distinctive trait as “disinhibition”. The desire to have a leader who says stuff without a filter, and who has the confidence to “move through the world without the behavioral inhibition most of us labor under”, and back their own judgment, has an appeal most people can relate to.

His spontaneity or “disinhibition” was at full display, for example, when holding a town hall in Pennsylvania, according to Klein:

What comes next is something I’ve never seen before. Trump, swaying dreamily to his playlist, in front of a rally full of people, for nearly 40 minutes. It was like he was D.J.’ing his own bar mitzvah. You can look, in these clips, at the faces of the people around him, like Noem. They really have no idea what to do. They are suddenly backup dancers in a concert that shouldn’t exist.

I have already written quite a bit about the increasing fakeness of academia:

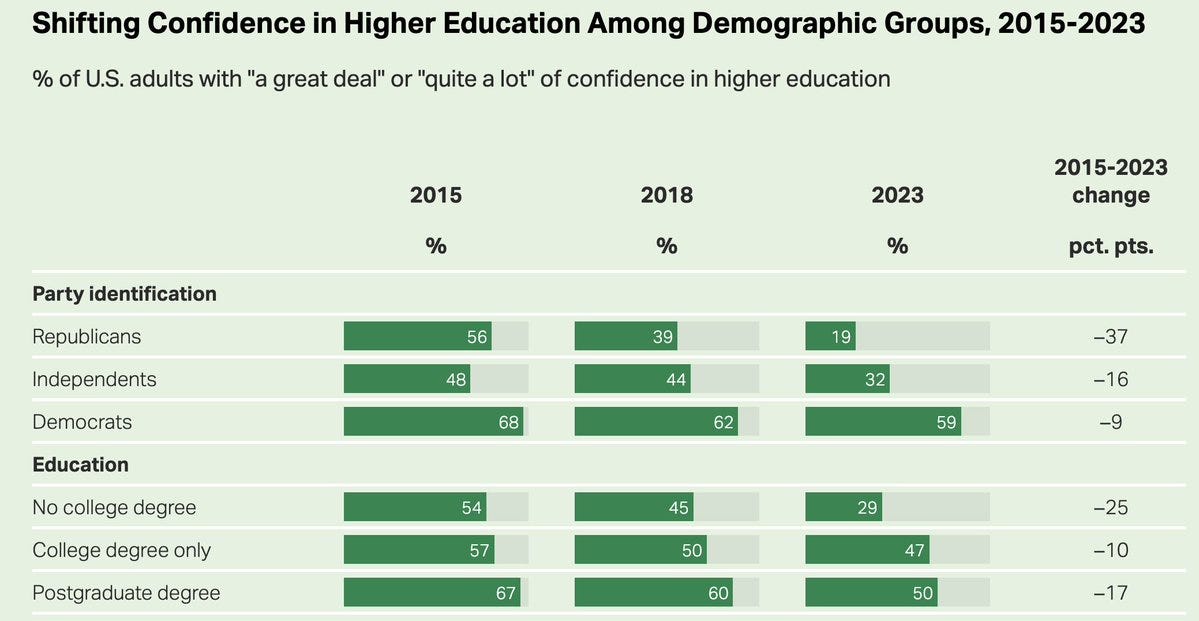

What do things like plagiarism, cases of research misconduct and data fabrication, sloppy science, the so-called replication crisis, nepotism, and declining trust in higher education have in common?

I claim they reveal the deteriorating state of contemporary academia—its increasing institutional entropy.

Due to the logic of Goodhart's law, all quality signals are subject to deterioration over time: after something becomes a signal of a quality or desirable characteristic (e.g. intelligence, conscientiousness, persistence, bravery, honesty etc.), actors appear who invest efforts in acquiring the signal even though they do not possess the quality or characteristics that justify possession of the signal. To the extent that they succeed in this, the signal loses its original signaling value.

Plagiarism, sloppy science, and cases of fraud are part of a wider story about the loss of the signaling value of higher education in general. They are indicative that academia increasingly selects for incompetence, people who might be good at ticking all the boxes but do not produce much value.

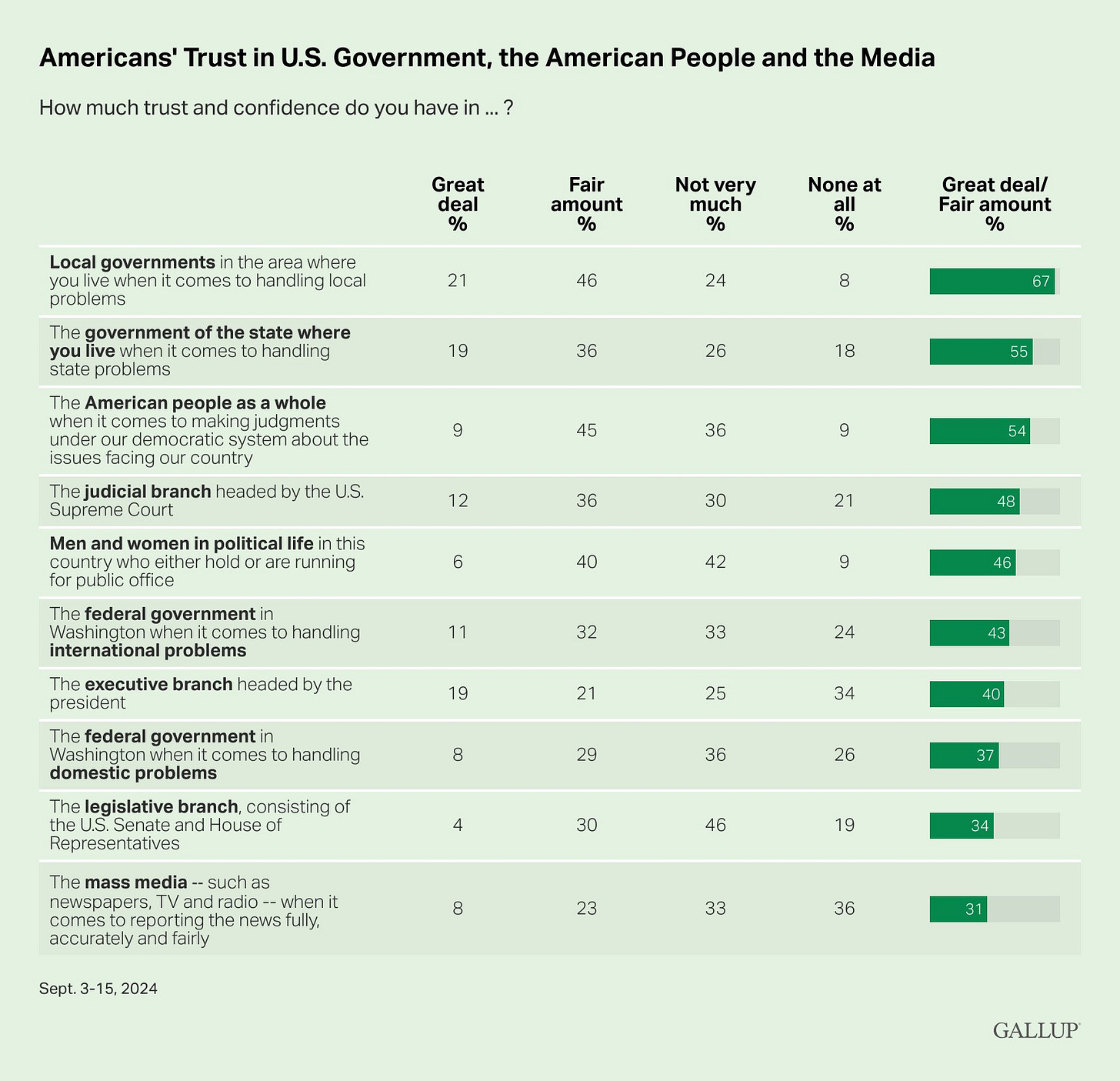

….and the fakeness of the news media:

The main problem with the modern news media is exploiting the underlying logic of communication, what relevance theorists call the communicative principle of relevance, namely that every communicative act conveys a presumption of its own optimal relevance.

In other words, when people communicate, there is an implicit expectation that the information shared will be relevant enough to justify the effort expended in processing it. This is patently not the case with most news in the media. With clickbaits, junk news and fake (or biased) news, the media is betraying the trust that communication presupposes. Declining public trust in the mainstream media follows as a consequence.

Incidentally, I started writing this post amid the debunking of a fake CNN report about a Syrian prisoner who was supposedly unaware that the Assad regime had fallen.

There’s a reason why Trump often criticizes precisely those groups that enjoy the greatest mistrust among the public.

Trust reflects trustworthiness. The standard way of dealing with declining public trust in institutions is to lament it and attribute some kind of irrationality to the public. From there it follows that nothing in particular needs to change, except perhaps hiring some "communication experts" to change the public's perception of reality. "Perception" because there is nothing wrong with reality.

However, declining trust basically means our evolved cheater-detection module is hyperactive as a result of the increase in the frequency of less trust-worthy individuals and/or behaviors that violate trust.

As Barbara Oakley puts it in her book Evil Genes, trust-violating behaviors are counterbalanced by lowering trust thus making the success of fakeness frequency-dependent:

How much these cheaters succeed depends on how many of them there are. If their numbers are tiny, they can easily find victims to dupe, and so they thrive. If their numbers grow large, however, the surrounding population grows more wary. In this more savvy population, it's harder to find a gullible target, and so the duplicitous have a more difficult time being successful—and being able to reproduce successfully. Thus there are fewer cheaters in the subsequent generation. And so it goes in a seesaw of counterbalancing activities, much like a predator-prey relationship.

The current wave of anti-incumbent sentiment that is sweeping major democracies seems to be favoring “disinhibited” types of politicians.

The present Croatian president, Zoran Milanovic, ran for his first term with the slogan “A president with character” while one of the slogans used while running for his second term was “Choose Croatia with an attitude”. It's no surprise, therefore, that Politico recently referred to him as the Croatian version of Trump.

Donald Trump will take office on 20 January 2025 replacing the incumbent president Joe Biden, a person whose whole presidency was shrouded in fakeness: the rumors about his cognitive decline turned out to be true, after all. Not only that but the decline was present from the very start of his term which is why his wife held events in more counties across Iowa than her husband during the 2020 presidential primary, as The Wall Street Journal reports:

Presidents always have gatekeepers. But in Biden’s case, the walls around him were higher and the controls greater, according to Democratic lawmakers, donors and aides who worked for Biden and other administrations. There were limits over who Biden spoke with, limits on what they said to him and limits around the sources of information he consumed.

Throughout his presidency, a small group of aides stuck close to Biden to assist him, especially when traveling or speaking to the public. “They body him to such a high degree,” a person who witnessed it said, adding that the “hand holding” is unlike anything other recent presidents have had.

But wait a minute! Didn't the legacy media tell us something similar about Putin—you know, the guy supposedly suffering from a brain disorder, blood cancer, Parkinson’s disease, multiple heart attacks, and who was on the brink of death or already dead and replaced by a double?

Was this all a projection?1

Pardoning his son after vowing to respect the court's decision was, for many, the final blow to Biden's credibility. It shattered the self-serving illusions cherished by Democrats—their claims to universalism over tribalism and nepotism, their assertion of standing for the rule of law and impartiality over lawlessness and bias, and more.

Domestically, the rule of law requires a more even distribution of power. As the economist Mushtaq Khan points out:

A rule of law requires a distribution of power in society, which is so broad-based that even the powerful follow rules, because there are lots of other powerful people who will not tolerate one of the powerful not following rules. But if the powerful are not very capable, they don’t need rules. And if they’re small in number, they can collude with each other and they will impose rules on everyone else, but they will violate the rules themselves. As soon as that happens, you don’t have a rule of law. And that’s why we describe the situation in most developing countries as rule by law.

Laws are enforced even when you don’t have a rule of law, but they’re enforced on those on whom they can be enforced. And those who can evade those, or bypass them, usually tend to get away. It may look like rules are enforced, but you might only have a very strong rule by law. And people often confuse that with a rule of law. A rule of law is a very, very specific thing. And only a very small handful of countries are close to that.

So when Biden claimed he would abide by the jury's decision, he was effectively betting that the Democrats' institutional dominance was strong enough to deliver the outcome he desired.

If he had gotten the decision he desired, the illusion that he was a man of principle would have been preserved. The army of propagandists and sycophants could continue repeating that Dems stand for the rule of law (even though they were wagering that the very conditions for the rule of law were sufficiently absent).

And if you stop following principles or rules when they start to conflict with your interests, is it not correct to say that you followed your interests all along? You simply benefited from the “coincidence” that your interests aligned with those principles—until they didn’t.

All this arrives at a time when the reality and nature of the "rule-based international order" are being increasingly questioned and scrutinized. Here too, it seems, that the illusion of being principled was maintained by the fact that it was you, and you only, who had a say in whether you were following rules.

But the social and public nature of rule-following consists in the fact that it is not only me who has a say in whether I am following a certain rule or not.

Here too, in the international order, you need a a broad distribution of power.

This is where the inside view meets the outside view.

It was clear from the start of the war in Ukraine that accuracy would not determine the type of information released but rather its desired effects. People in the media knew that (or should have known that) but went along with it. In an NBC piece from April 2022, we are told that “Multiple U.S. officials acknowledged that the U.S. has used information as a weapon even when confidence in the accuracy of the information wasn’t high. Sometimes it has used low-confidence intelligence for deterrent effect, as with chemical agents, and other times, as an official put it, the U.S. is just ‘trying to get inside Putin’s head.’ ” Remember that quote from Walter Lippmann and Charles Merz about New York Times’ reporters being too credulous vis-a-vis State Department? That was in 1920.