Harvard's Plagiarism Scandal Reveals a Deeper Truth About the Educational System

You cannot resolve a "people problem" by treating it as an "incentive problem"

What do recent academic scandals involving Claudine Gay, Francesca Gino, Lisa Cook, and Dan Ariely have in common?

What do things like plagiarism, cases of research misconduct and data fabrication, sloppy science, the so-called replication crisis, nepotism, and declining trust in higher education have in common?

I claim they reveal the deteriorating state of contemporary academia—its increasing institutional entropy.

Due to the logic of Goodhart's law, all quality signals are subject to deterioration over time: after something becomes a signal of a quality or desirable characteristic (e.g. intelligence, conscientiousness, persistence, bravery, honesty etc.), actors appear who invest efforts in acquiring the signal even though they do not possess the quality or characteristics that justify possession of the signal. To the extent that they succeed in this, the signal loses its original signaling value.

Plagiarism, sloppy science, and cases of fraud are part of a wider story about the loss of the signaling value of higher education in general. They are indicative that academia increasingly selects for incompetence, people who might be good at ticking all the boxes but do not produce much value.

As I previously wrote, the IQ-signalling ability of higher education is weakening.

Additional support for this trend comes from a new meta-analysis that indicates the IQ of university students and university graduates dropped to the average of the general population.

Imagine earning your diploma or your PhD by investing in hard work and abilities only to find yourself one day realizing that they are practically worthless as signals of that effort and those abilities. After all, if everyone has a diploma, no one does!

Well, at least we are all educated, right?

The not-so-curious case of Diederik Stapel

The Dutch psychologist Diederik Stapel fabricated a lot of data over a long period of time, resulting in 58 of his publications being retracted. He knew how to navigate the left-leaning academic corners of social psychology producing studies that confirmed its political biases and sensibilities. He published on stereotyping, discrimination, and selfishness of carnivores (compared to vegetarians). Stuff like that.

One might say he knew how to push the right buttons—except the right ones were the left ones.

After he was exposed he published a book-length memoir whose very title Derailment anticipates that the explanation of his fraudulent behavior will be given in terms of situational, not dispositional, factors: he lost his way, poor fella, started to take shortcuts, “one thing led to another” and then found himself more and more often in completely the wrong lane.

It's not him, you see, he was simply under pressure of The Situation.

However, after the book was published the reviewers noticed odd similarities between parts of Stapel's memoirs and the works of Raymond Carver and James Joyce.

Poor fella, derailed yet again.

One could have argued: "Surely he would not plagiarize other people's writings since he will be under close scrutiny given his prior track record of faking studies. Surely he would be disincentivized to cheat again once he got caught and publicly shamed.”

Well, herein lies lesson number one: “incentives matter,” as economists like to say, but only against the background of personal characteristics that determine in what way, exactly, incentives matter.

And for lesson number two? Well, cheaters gonna cheat. Stapel had no need to copy Carver's and Joyce's writings. He was under no pressure to publish his book to, say, keep his job. He was simply a narcissist eager to get a narcissistic supply. The way he wrote the book is a testament that the “situational” explanation of his own past behavior, espoused in his book, was—false.

Confusing the “people problem” with the “incentive problem”

The funny thing about Stapel is that after being dismissed from Tilburg University, he got a new position at a vocational university. His job? Helping other researchers.

It seems committing academic fraud doesn’t carry much downside.

Indeed, as Kyle Galbraith from the University of Illinois, found out, this is a part of a general pattern. In a paper titled Life After Research Misconduct: Punishments and the Pursuit of Second Chances, he finds that about half of the offenders are allowed to keep working even after being caught for outright fraud.

“Those researchers have received more than US$123 million in federal support for their post misconduct research efforts”, he writes.

People like Stapel underscore an important point which is that contemporary academia has a “people problem”. However, it confusingly treats a people problem as if it was an “incentive problem”.

The confusion between the two leads people to search for a solution in micromanaging science—which leads to expanding bureaucracy.

But tweaking this or that incentive cannot resolve the underlying issue because the underlying issue doesn’t lie at the level of incentives.

First of all, there is only so much one can do with designing an appropriate incentive structure that actors in academia will be faced with. To take an obvious example, producing path-breaking work in physics cannot be achieved by scientists of lower intelligence even if you incentivize them to do so. You can try all you want but you won’t get there since an inability to produce such work from such a person is not a matter of deficient incentive structure.

Second, incentives, once in place, get subjected to Goodhart’s law: performance metrics are gamed thereby producing unintended effects. There are many examples of that:

But the problem of creating the right incentives to get the desired behavior within the system is minimal when the right people make up the “system”. For the proper functioning of the institution, not only the rules regulating the behavior of its members are important but, crucially, the members themselves, on whose characteristics the success of the rules depends.

As Trevor Blackwell put it: “People who want to do science purely for the joy of finding things out are a tiny minority of people. Academia didn't need to get its incentives right when it was just them involved, but in the last couple of generations it's grown beyond that.”

Real science is the result of certain types of people getting together to do their thing. When you incentivize the entrance of people who lack the relevant traits, or when you fail to attract or retain people with the relevant traits, we get bad science.

Cognitive capital flight—>sloppy science & research misconduct—>public distrust of academia—>prestige of science declines —>repeat

The type of people that the academia increasingly selects is that of a hard-working and ambitious, albeit risk-averse and not too intelligent and creative, poseur. One possible consequence is the reported decline in “disruptive” scientific papers.

Many valuable social institutions seem to follow a similar pattern of deterioration: they gradually accumulate members who differ in ability and character from the people who founded the institution and made it worthy of respect and trust.

Competence and networking

Irrational situations are often the result of many small decisions by numerous actors that are individually rational for the actor, but whose consequences accumulate over time and give collectively irrational outcomes.

In each hierarchical structure, or order that allocates status depending on the position in the structure, actors who strive to advance in the hierarchy have to possess skills that produce competence and networking.

“Competence” is a measure of how well a person “gets shit done” (good proxy: IQ).

“Networking” is one’s social capital, the number of relationships one has, the amount of people one knows, and can influence.

To advance in the academia, a person must publish papers. That requires some level of “competence”.

But he must also be a political actor: be a member of an influential academic clan, push the right political buttons (like Stapel), flatter the patrons, create debtors, and recruit followers. This is “networking”.

To maximize his position in the hierarchy, an actor cannot choose totally incompetent associates and followers; he cannot control irrational people, they embarrass him, etc.

On the other hand, if the associate is too competent, he can overshadow his superior. That's not good either.

A less competent actor must demand greater loyalty from the subordinates who will save him when his incompetence comes to the fore, whether it comes in the form of plagiarism (like in Gay’s case) or data fabrication (as in Stapel’s case).

If everyone was guided only by the criterion of competence (meritocracy), the incompetent would eventually be kicked out of the game, so it is in their interest to create debtors, i.e. actors who will prioritize loyalty over truth and competence. Something like Aristotle in reverse, favoring his friend Plato over truth.

If an actor chooses only according to merit (competence), and not according to loyalty, he risks his favors will not be reciprocated. Moreover, there may be an additional incentive to choose an inferior candidate because the inferior candidate knows that he is a debtor and that he must repay the favor. A competent actor, on the other hand, may think that he got his position solely due to his competence and therefore “owes nothing to anyone”. This introduces risk.

Since trust and loyalty are strong among relatives, the risk of not repaying favors is also reduced by the nepotistic selection of associates. This is especially a problem in more clannish countries.

This process describes what we call negative selection or cronyism.

In the long run, it is probably the case that “networking” outcompetes “competence”. People with traits that yield better “networking” (agreeableness, loyalty, nepotism, groupishness, conformity, etc.) outnumber people with traits that yield “competence” (e.g. intelligence). This is why institutions and systems deteriorate with time. Pressure for greater competence comes from the outside.

Misallocation of human resources and trust

Signaling enables sorting which takes place not only in the sense of choosing optimal social partners but also in the sense of “putting the right people in the right place”. That is to say, life in society does not only entail deciding who will be our friends and allies but also deciding who will be presidents, ministers, parliamentarians, judges, doctors... which person will have which role, which position, and which responsibility.

To establish a competent system, the designated roles should align with the competency of the individuals assigned to them. Yet, when signals of competence are corrupted, it results in the misallocation of human resources, a mismatch where individuals are placed in roles that are not suitable for their abilities.

The perception that the wrong people are in the wrong places in turn creates frustration and resentment.

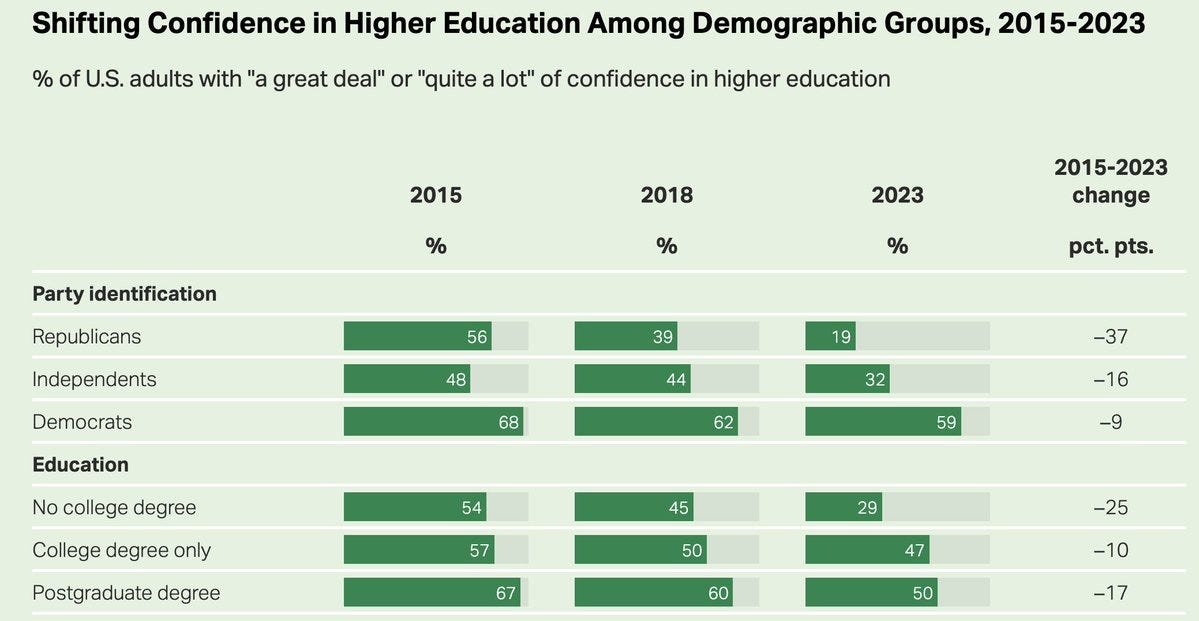

The result is a decline of trust in institutions.

Why should the public trust them knowing the quality of the people in them? Why should people trust them when they feel the signals of quality are corrupted?

And then when a pandemic occurs, the successful management of which requires citizens' trust in institutions, all that loss of trust, all those accumulated consequences of negative selection, come to levy a price.

Preserving the credibility of quality signals is one of society's greatest tasks. The absence of a way to identify quality and distinguish it from non-quality carries with it a huge social cost. Just as artificially formed prices lead to a misallocation of resources, so signals that have lost their informational value lead to a misallocation of human resources.

The academic arms race

Once the signals of quality get diluted by the ever-expanding circle of education, those whose abilities warrant the acquisition of signals now have to “jump” even more academic hurdles to distinguish themselves from lower-quality people with the same degrees.

Or they leave academia disillusioned with what the system has turned into. Physics PhDs become Wall Street’s quants.

Universities increasingly treat students as consumers; they are in the business of providing students with a pleasant experience where they should be protected from controversial or unpleasant attitudes and ideas that could spoil that experience (“safe spaces”). The telos of truth is replaced with a new telos of social justice.

Social justice, networking, and pleasant experiences go well together.

As a consequence, employers are putting less and less weight on the formal education of job candidates.

Many parts of academia function like Potemkin's villages. Students pretend to learn valuable knowledge while professors pretend to impart to students valuable knowledge. Parents pretend they're enabling their kids to have a better future, while politicians brag about education statistics. It is startling to realize how much (self)deception is required to keep the whole system going.

The additional jumping of academic hurdles undertaken to differentiate from other actors has other consequences, one of which is the delay in starting a family, something that is related to the observed trend of more educated people today having fewer biological children.

Given that genetic factors play a role in educational success, and that more educated people leave fewer offspring, an intriguing question arises: What impact does the credentials arms race have on the level of gene frequency in the population? Could an increase in years of formal education lead to a decrease in the genetic potential for actually being educated? That would suggest a paradoxical situation where a population, as it gains more and more years of formal education, becomes less and less able to cognitively profit from it.

In one of the classic examples of an evolutionary arms race, trees grow taller and taller as they compete with each other for sunlight. Another example where individual rationality does not lead to collective rationality.

This competition is wasteful and the entire ecosystem—as well as the trees themselves—would be better off if it were smaller because they would consume less energy needed to maintain massive trunks.

The problem is that an agreement on mutual limitation of growth is impossible. And even if that “agreement” were to be reached by any chance, it would not be evolutionarily stable, because the first mutant tree that would not adhere to the agreement would gain an advantage over the others and thus restart the upward race.

People are facing the same problem. According to one study in the United States, the average level of education within 500 occupational categories increased by 1.2 years from the early 1970s to the mid-1990s even though most jobs did not change significantly during that period. As people become more educated, an individual needs more education to convince an employer to give him a job.

An agreement on mutual limitation seems to be difficult to achieve here as well: masked by the glittering gloss of mythology about the “transformative” effects of education, too many interest groups and livelihoods depend on the maintenance of the status quo. The result is a wasteful race where participants have to run in order to stand in the same place.