The battle for the world chess championship is over. It was an event where players were trying to remember moves from their computer-guided preparation while commentators were using computers to evaluate the accuracy of those moves. Spectators, meanwhile, were able to infer which player is better, as well as the quality of each move, by observing a computer-generated evaluation, which was represented graphically through a bar display. Who’s winning? I mean, just look at the bar!

Ok, not quite, but there is some truth to it. If it were completely true, it would constitute the World Chess Championship's version of the situation described by the Chinese room argument, except there was also a Russian in the room next to a Chinese, Ding Liren, who ultimately became the 17th World Chess Champion.

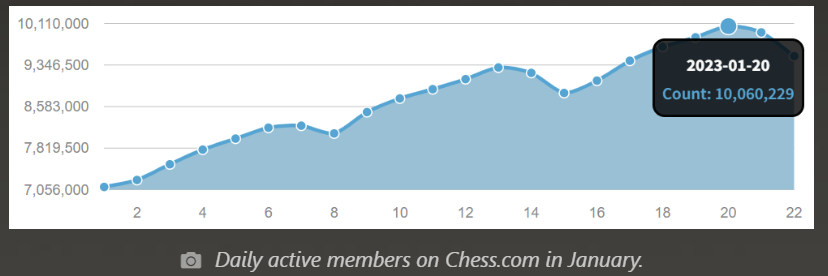

The recent boom in the popularity of chess can be traced to several factors such as the pandemic coupled with the booming chess streaming scene (Twitch and YouTube), Netflix, and prestige bias.

The pandemic made people stay at home more while the chess streaming scene and Netflix made it easier to turn to chess as a way to pass the time and stay connected with others.

The last one—prestige bias—refers to the tendency to imitate cultural models that have more prestige. To be specific, it turns out that the most popular social media post in 2022 featured Messi and Ronaldo playing chess in a Louis Vuitton campaign. This matches in time with an uptick in the search for the word "chess", as shown by Google trends. FIFA World Cup 2022 event was an amplifier for the circulation of the photo, and—as a byproduct— of chess as well.

The previous boom in the popularity of chess, at the end of year 2020, matches with the release of Netflix's The Queen's Gambit.

If chess could build a person's character or be some kind of practical guide in life, some useful life lessons could be drawn from it. So for those who are new to the game, here is a list of some of those lessons, a list that I will be updating over time, so consider this post a “work in progress”.

Chess punishes the lack of perspective-taking

Chess punishes failure to consider the opponent's perspective. It's not clear what playing chess would even look like if you didn't have to think about what your opponent could do next. The game is such that it penalizes your assumption of the other player’s irrationality to the extent that the other side is a rational player.

This makes the assumption of rationality pragmatically justified: the assumption of an irrational opponent has a higher potential cost than the assumption of a rational opponent. If you assume a rational opponent, and he is not one, you will lose nothing (except possibly some time required for thinking). If you don't assume a rational opponent, and he is one, you lose the game.

A person can be as motivated to misinterpret his opponent's moves, but in the end, he has to pay the price.

Mistakes are bad only if your opponent can spot them

Unless you are a perfectionist, your moves are bad only to the extent your opponent is able to capitalize on your mistakes. If you are playing for the win, your moves don’t have to be perfect, they only have to be good enough.

What is “good enough” depends on the strength of your opponent: if you play with a weak player, you can afford more mistakes than with a strong player and so you do not have to be as vigilant. Adjust your game to your opponent’s strength. If you do not know your opponent’s strength at the beginning of the game, start with the assumption that he is a strong player and adjust your model during the game.

Losing something valuable is not always a bad thing

Chess may teach you how easy it is that one player's good fortune can turn into a demise while the sacrifice shows how losing a valuable thing is sometimes good for you.

Both are illustrated in the figure below.

Criticism presupposes the ability to provide an alternative course of action

Distinguish between a move and a position. People often conflate the two when they are criticizing something. If you are criticizing a particular move in the game, you must be able to formulate a better alternative: “Bad move, you say? Compared to what?”. Otherwise, it is not the move that you dislike but rather the position you are in.

Since a position is a result of a series of moves from both players, a better alternative position is more likely to require a change in a move that is already long “buried” within the game and whose consequences are hard to reverse. On the other hand, if you notice a mistake in the move you just made, it is more likely you can fix it. Regret makes more sense while you are still able to rectify your mistakes or missed opportunities.

The beauty of things is often hidden (Or: Reality sits on top of eliminated possibilities)

The beauty of a particular chess game often consists in what in fact did not happen but could have happened, and it is precisely this "could have happened" that explains what actually did happen on the board. Every move presupposes the elimination of, at least some, alternative options. The difference between an amateur and a professional is that the second is able to correctly explore many more possible worlds and find the optimal one.

This also means that the beauty of a game will remain hidden from the eye that is not well-versed in seeing all the hypothetical worlds on which the real one is built.

Bluffing is the privilege of the powerful

Even in chess, which is a perfect information game, there is bluffing. So for example, Nepomniachtchi was bluffing with a 31. Qh4 move against Ding in round 8 of WCC.

How come that Ding fell for it? Well, the lesson is that making a threat makes the most sense against the track record of demonstrated competence since that is when your credibility is the highest.

Political scientist Hans Morgenthau defined prestige (or what we today might call status), as a reputation of power. "In the struggle for existence and power, which is, as it were, the raw material of the social world, what others think about us is as important as what we actually are," he wrote in his 1948 classic Politics Among Nations.

Bluffing as a strategy makes less sense for a weak player that doesn’t have a “reputation for power”. A strong player, on the other hand, who has demonstrated his quality during his career, will be feared more and thus can use this strategy more effectively to his own advantage. This is why Magnus Carlsen recently said:

I think the most important thing that I have realized over the years is that lot of people fear me. I learned to use that against people. Specially once you realise that your opponent is not mentally prepared to play for a win, then you can take lot more chances.

During games, sensing your opponent's mental state is very useful. For instance, take my games against Wesley So, specially in shorter time controls, you can see, I am always giving him chances to play risky moves and he almost never takes them. This means that I have a massive psychological advantage playing him. He is an amazing player and his understanding (of game) is probably not worse than mine but I am able to push him around because he is not willing to take risks.

Not being willing to take risks is an extremely risky strategy because it means you will get pushed around and bullied basically.

The “game” often starts before the game

Daniel Naroditsky once told the story of his chess opponent being 58 minutes late to a chess game. Now there is a rule that if your opponent is an hour late, he forfeits the game. Daniel was already tallying his first point in the tournament, ready to sign his score sheet when his opponent suddenly came along and totally destroyed him in the game.

After the game, his opponent tells him, "You know, there is an old Soviet trick. If your opponent is an hour late, you just wait an hour on the first move to equalize time.” The logic is that having an extra hour moderates your expectations, creating a psychologically unsettling pressure that you have to win easily since you have an hour advantage. This pressure makes you slip up so the best thing may be to counterbalance its effect by waiting an hour on your own first move.

Self-handicapping may improve your position

While we’re on the topic of psychological tricks a player may use to gain an advantage over an opponent, consider the case of Bongcloud opening where a player self-handicaps by making an obviously bad move. This may be a rational strategy because it changes the payoff matrix: the downside/upside of winning/losing is not the same for both players.

If you as a self-handicapper win the game, your win means more in the eyes of the spectators since you won despite your handicap. But if you lose the game, you already have an excuse— after all, you played with a handicap! Your opponent’s win provokes a “well, of course he won” reaction while the embarrassment he will be faced in case he doesn’t win despite the huge initial advantage may create pressure that eventually leads him to make a mistake.

Asymmetric payoff matrix was perhaps the reason why Hikaru Nakamura, playing as Black, responded with a self-handicap of his own after Magnus Carlsen opened with a Bongcloud (1. e4 e5 2. Ke2 Ke7) in a game the two of them played in 2021. One could almost say that Nakamura knew the old Soviet trick and equalized the handicap.

Like in the previous example, self-handicapping burdens your opponent with the feeling that he has to win easily but note that, unlike the previous example, here it is apparent to your opponent that you created your own handicap intentionally while it wasn’t clear to Naroditsky that his opponent is being late on purpose.

In other words, a handicap is advertised by the player— by handicapping himself he is signaling that he is strong enough to afford to play with a disadvantage which may appear disrespectful to the opponent. However, as is the case with bluffing, self-handicapping is mostly the privilege of the powerful. Do not abuse it.

There are many cases that show how self-handicapping can work to one’s advantage, such as the evolution of the peacock tail or, perhaps, the evolution of emotional tears, a topic of my previous post.

Good moves trump mind games

Bobby Fischer, one of the greatest chess players of all time, was famously quoted as saying, "I don't believe in psychology, I believe in good moves."

For all the talk of psychological tactics, mind games, and mind tricks one could use to throw opponents off their game, nothing beats good moves. Indeed, as we have already seen, effective usage of a lot of these psychological tactics—like bluffing and self-handicapping—presupposes competence. Your threats and bluffs are credible insofar as you have a reputation of being a competent player that is able to realize those threats.

Fischer was a pure chess player who believed that the best way to win a game was through strong moves on the board, not through psychological tactics. Stockfish, the most popular chess engine, might agree since “psychology” plays no part in its play. But for humans who are less perfect and eager to win the game, resorting to mind games will be inevitable. All is fine so long as you do not start hiring people to hypnotize your opponent!