Artistic Authenticity in the Age of Artificial Intelligence

Where does the intuition that AI-generated art lacks authenticity come from?

So one day you find out your favorite song was actually produced by an AI. You thought the author was a person whose name and life were familiar to you. Indeed, you got acquainted with the author's biography precisely because his music touched you deep inside.

But as it turned out, that person simply used a program to generate the music.

Do you think your attitude toward that song would change? If so, in what way?

What about a painting or a piece of writing?

Your favorite influencer?

Our experience of a work of art seems strongly influenced by factors that are external to the work itself: knowing something about the author, his or her life, when and where you first consumed that work of art, with whom, and the like. For example, one study found that older adults liked songs from their adolescence more than other songs. That kind of music was associated with more autobiographical memories.

When AI is concerned, there is an intuition that AI-generated art would lack “authenticity” and— perhaps consequently—that it would not deliver the same degree of pleasure as human-produced art.

Is it likely that AI singer-songwriters, like Anna Indiana, will become as popular as their human counterparts, and not just out of curiosity?

Her music is not much worse than many other popular performers. If the material artefact (the sound you here) is the only thing that is important in appreciating artwork, there should be no obstacle to her popularity.

But appreciating a piece of art is not simply about appreciating the artefact itself, i.e. the end product of an artistic process. Implicit in appreciation is the evaluation of its very creator; his abilities, skills, interests, values, and preferences—all of which are inputs to our coalitional psychology1 that tracks information relevant to a person’s suitability for being a group member or social partner in general.

Suno AI says it’s “building a future where anyone can make great music”. But do we really want to live in a world where anyone can make great music? Isn't producing music a way of distinguishing yourself, showing your (otherwise) hidden talents and traits, part of the signaling-and-sorting game?

Do we want a future where everyone plays chess as good as Magnus Carlsen?

Signaling and Sorting

Implicit evaluation of the author as an integral part of appreciating art is in line with some hypotheses about the origin of the art instinct in signaling. According to that account, art could be seen as a communicative process that is embedded in our social interactions since “it is a stimulus intentionally emitted to convey information to others (about the sender or the environment) and influence their behavior”.

In her work with San hunter-gatherers, Polly Wiessner noticed that the items of material culture that effectively portrayed individual identity were visible personal utensils and body ornaments (Wiessner, 1983). In addition, she observed that the labor invested in ‘artifying’ an object not only added aesthetic appeal but also signaled the positive personal qualities of the maker, such as initiative and skill, which are traits that are sought-after in a cooperative partner. Therefore, displaying visually attractive items on the body, such as shell beads, would be highly suitable for the function of signaling one’s identity while simultaneously advertising one’s positive qualities to potential collaborators. Another advantage of signaling identity through visible social markers like body ornaments is that it reduces the risk of aggression from strangers, who are able to tell at a glance whether the unfamiliar individual is an ally or a foe, helping foresee and avoid potential conflict (Eibl-Eibesfeldt, 1988; Kuhn & Stiner, 2007).

The proposal that early personal ornaments arose as a cultural strategy to mediate relations in emerging cooperative networks beyond the intimate group seems to fit the observation that the appearance of beads correlates with increases in group sizes and the intensification of interactions throughout the Pleistocene. For most of human evolution, people interacted only in small networks, for example in a (extended) family unit, within which every member knew each other well, so there was no strong pressure for signaling identity. Consequently, we would not expect to find evidence for social markers. However, whenever these small groups started interacting more frequently and with more distant groups, the subtle signaling of individual identities through personal ornamentation became relevant, leaving a tangible trace in the archaeological record.

This is from psychologist Larissa Straffon.

The idea is that visual art practices, at first, develop to signal individual identity to manage social relations in a cooperative network larger than the family group. As the cooperative network expands in number and geography, visual art starts to signal collective identities:

Social markers have a minimum efficiency value. At the level of the intimate network they are unnecessary because in these small groups, identity is a constant (Dugatkin, 2002). In contrast, when network size grows and brief interactions with strangers increase, the group becomes too large for individuals to manage by direct personal interactions. It is in this context that social markers may become useful and necessary. As Wobst suggested (1977), social markers work best among strangers at a ‘middle distance’ of social relations, that is, individuals who share the same cultural ‘codes’, but do not know each other personally (Gärdenfors et al., 2012; Kuhn & Stiner, 2007). At this ‘middle distance’, social information becomes clearly impportant for deciding whether or not to interact and cooperate.

In this way, early visual art in the form of personal ornaments culturally extended human memory capacity, allowing Pleistocene groups to expand their cooperative networks, and helping manage emerging social relations beyond the immediate familiar group.

Whether this particular hypothesis holds up historically or not, it does seem true that art can be used to express individual and group differences, i.e. serve to signal individual and collective traits and/or identities.

We know that individual psychological differences are correlated with different art preferences. For example, research from 2022, involving more than 350,000 participants from over 50 countries, found universal links between musical preferences and personality:

Across the world, without significant variation, the researchers found the same positive correlations between extraversion and contemporary music; between conscientiousness and unpretentious music; between agreeableness and mellow and unpretentious music; and between openness and mellow, contemporary, intense and sophisticated music. They also identified a clear negative correlation between conscientiousness and intense music.

Similar correlations are found between personality and movie and literary genres.

If a certain type of music is correlated with certain personality traits, then producing, performing, or simply consuming music may be a good way to advertise one’s own traits and identify similar types of people with whom one can form bonds, partnerships, and coalitions.

People generally prefer people similar to themselves. Assortative mating and friending. In a world where we are scattered all around and where people don't have “what they are like” written on their foreheads, mismatching inevitably occurs. Solving the sorting/matching problem requires signaling— which is a condition for finding optimal social partners. Without it, we run into other people, collide and bounce off each other like billiard balls. Only occasionally does a match occur. Signaling makes sure that “matching” happens much more often than “sometimes”—it makes the matching process so smooth that we take it for granted. Kind of like the force of gravity—it's so fundamental to our way of life that we don't realize it's a condition of it. The importance of its presence is best seen only when it disappears.

In that sense, it is interesting to note that music preferences are peculiar in one regard: unlike some other preferences, say food preferences, people can get very disappointed when other people, especially those close to them, dislike music they find dear. That may be because, on some level, there is a perception that dissimilarity in music preferences reveals deeper behavioral dissimilarities between people and their characters.

And we know things get “deep,” as it were, since the process of sorting leaves a trace on our genome. In his book Blueprint, Nicholas Christakis writes that in his lab he used:

data from 1,683 unrelated heterosexual spousal pairs and examining over one million genetic loci, we explored whether genotypic assortative [seeking similarity] or disassortative [seeking contrast] mating occurs across the whole genome.. We found hundreds of genetic loci across the genome that exhibited more assortativity or disassortativity than would be expected due to chance... And we found that loci exhibiting even moderate assortativity among spousal pairs were evolving faster than loci exhibiting no assortative mating or those exhibiting disassortative mating. In other words, something about assortative mating may enhance the fitness of humans and thus increase the prevalence of the relevant gene variants... Overall, people in our sample chose partners from the population at large who were genetically equivalent to fourth cousins.. Couples who were more closely related (such as first cousins) had fewer surviving offspring, as did couples with too little similarity.

As with our work analyzing spousal pairs, we found that friends tended to be significantly more genetically similar than strangers drawn from within the same population... That is, when people are left to choose friends among a group of people to whom they are not actually related, they have a discernible, if slight, preference for people who resemble them genetically.

Our analysis yielded a further supportive insight regarding the survival advantages of friendship. We found that, overall, across the whole genome, the genotypes humans tend to share in common with their friends are more likely to be under recent natural selection (over the past thirty thousand years) than other genotypes.

But let’s get back to the issue of the work of art.

It is not simply the case that our knowledge about the author can influence our experience or understanding of artwork, the very assumption that there is authorship present behind an artefact, that is, an agent who wanted to communicate something with it, is crucial for the interpretation of the artefact itself. Indeed it is crucial for interpreting that artefact as a piece of art.

To illustrate that point consider the following example.

Watching through the window, you see a black cat crossing the street. You will not assume that this fact will be relevant to something that will happen later.

But if you see the same exact scene on a screen, within a movie, you will probably be justified that this event will be relevant for something that will happen later. Moreover, the filmmaker may intentionally violate the viewer’s expectation of relevance to achieve a certain effect on the viewer.

The fact that people have a strong preference that a certain person—an artist—is linked to the artwork is manifested in the following observation: although people could save a lot of money if performers weren't present at the stage during concerts and instead their music was played from a recording, people still prefer the presence of the author performing live music in front of them.

Types of Agents, or: Is it Reasonable to Accept a Promise from Superman?

A promise is a type of agreement that typically carries uncertainty with it. Uncertainty means risk. And taking a risk—to the extent it involves other agents— requires trust. Thus, accepting a promise from another person is a matter of trust—it makes no sense to accept a promise from a well-known liar.

Now consider a question I picked up from philosopher Daniel Dennett: is it reasonable to accept a promise from Superman?

Sounds silly but think about it for a moment.

An agent who is not vulnerable (forget about Kryptonite for a second) stands to lose nothing if he doesn’t keep his promise. Breaking a promise is something we react to with some kind of punishment, but how to punish someone who is not vulnerable? Can you trust an invulnerable agent? It seems all the risk is asymmetrical in case you accept a promise from such an agent.

Note that the question is not can you say “I accept a promise”. Of course, you can say it. That is not the issue.

Can you threaten Superman or blackmail him?

Again, the question is not whether you can say “I will kick your ass if you do not do X” to Superman. Of course, you can. The question is does it make sense to say it?

Does it make sense to threaten a bacteria? How about a dog?

Does it make sense to accept an apology from a person who cannot change his or her behavior, the behavior for which (s)he is apologizing?

The point of this exercise is to highlight that our ordinary practices of making/accepting promises, threatening, apologizing, etc. are underpinned by features of the world—which includes features of agents, like vulnerability—that may be violated or absent under certain circumstances. In such cases, the question arises whether it is meaningful or reasonable to accept or make a promise, threat, or apology.

What Kind of Agent is AI?

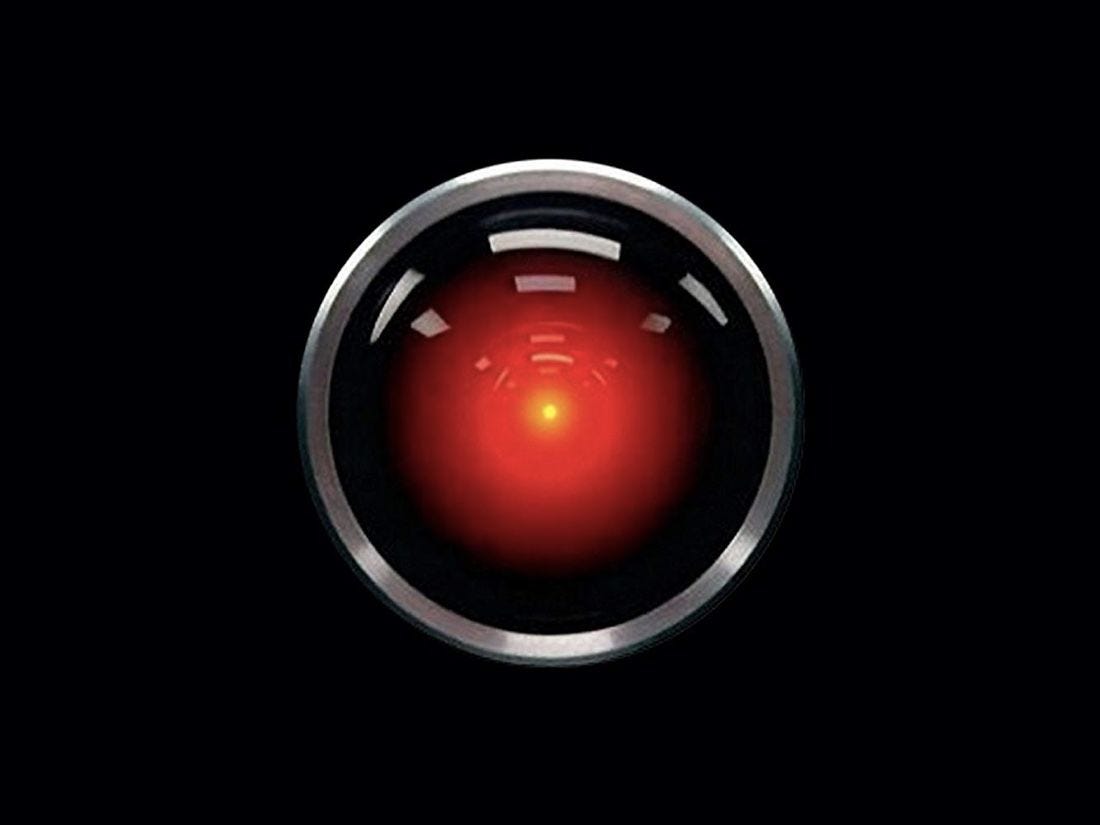

What does this have to do with AI-generated art? Well, with AI we don't really know what we're up against. We don’t know what type of agent is behind the art. Is it an agent at all? How similar to us is it?

The question of similarity is relevant because interpreting a piece of art is often influenced by what we believe the author believes, whether we believe we share the same assumptions about the world or believe we have the same background knowledge.

Likewise, similarity in behavior is the basis for the interpretation of other agents. As I pointed out in my previous post, in the absence of sufficient similarity between minds, people’s thinking about the minds of others results in typical mind fallacy.

Imagine if some AI generated an image like the artist Mark Rothko’s painting No.14. Would the viewers interpret the colors as representing different emotional states or metaphysical concepts? Would they view the painting as a meditation on the human condition, the spiritual realm, or the experience of existence itself, as was the case with Rothko’s aficionados? It’s hard to say since in that case the viewers would not know much about the AI’s beliefs or whether it has beliefs at all.

What we can say with certainty is that AI singer-songwriter Anna Indiana is not an agent who is capable of being a social partner in the sense that matters to us; she cannot provide support, make a promise, or apologize. She cannot be a social partner. Her level of competence is not that high.

And to the extent that appreciating and enjoying a work of art is about being part of a process of evaluating potential social partners, there will always be a feeling that something is missing when AI-generated art is concerned—an intuition that it lacks “authenticity”.

Dissociation

In “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1935), cultural critic Walter Benjamin argued that the advent of technologies like photography, film, and other mechanical reproduction techniques that allow art to be replicated and distributed on a mass scale, strip the original artwork of authenticity and “aura”, i.e. the sense of awe and reverence that surrounds an original work of art when experienced in its specific time and place. Copies lack the unique presence, history, and context of the original, impacting the viewer's perception of the work.

The specific time and place from which a work of art originally emerges provides the audience with a context for interpreting that art. The context informs our understanding and appreciation of the art in a similar way that our knowledge of the author informs our understanding of the art.

(The point here is not that this is necessarily so: one can appreciate artwork without knowing anything about its author and its cultural context. The point is that to the extent that this knowledge is available, it will influence one’s experience. Consequently, the same artefact can elicit different interpretations and different levels of enjoyment from the audience depending on the availability of that knowledge.)

In the environment where our art instinct evolved, a piece of art was typically connected with its maker or holder. Personal ornaments were connected to the person wearing them while body art was connected to the body of its owner. There were no music records— which means the music was always connected with the performer, and which member of the tribe painted an image on a cave was probably common knowledge within the tribe.

So there was always some kind of link between the author and the artwork, and that link allowed observers to make certain inferences: to infer something about the author by using artwork as a piece of evidence, or, conversely, to infer something about the artwork by knowing something about its author.

If with mechanical reproduction an artwork became increasingly divorced from the cultural context from which it emerged, perhaps we could say that AI-generated art further dissociates artwork from the author—it dissociates the artefact from being embedded in the social game of signaling and sorting.

In that sense, AI-generated art deprives us, observers, of indulging (satisfying) our curiosity about the author since there is a feeling that there is really no one there to be evaluated.

Behind that kind of art, there is no agent capable of being a social partner in the sense that matters to us.

At least for now.

John Tooby, one of the pioneers of evolutionary psychology, talks about coalitional instincts as a set of programs in our brains that “enable us and induce us to form, maintain, join, support, recognize, defend, defect from, factionalize, exploit, resist, subordinate, distrust, dislike, oppose, and attack coalitions.”

This was illuminating and interesting, thank you! As a songwriter, I hope you are right that AI cannot entirely replace humans for the compelling reasons you suggest. But mass production and replication of art in film and music and images DID partially replace this connection and made it normal. People still obsess with knowing about the artist behind the art, but they don't need to hear that artist live. I saw a movie recently about Paul McCartney made some time back. I learned that it was he, not John, who was initially into avant-garde music and art. That is not the story presented generally about Paul McCartney. It doesn't change how much I like some of his songs, but it framed him differently and made my relationship to the music shift subtly. For me, it was a validation of my judgements, for others, it might feel dissonant with how they want to see him. But like most people, I don't know Paul McCartney, and have never seen him play live. Like everybody, even the oldest people alive, I grew up in a time of mass produced music. I have often wondered if this is really what we need most from music. And I love the process of recording and producing my own music, but I still have those questions. I believe nothing ever will replace live music played by human beings in intimate settings, as that is how we evolved. With any technology "advance," it seems we give up as much as we gain, maybe more. As our brains and culture become used to AI generated art, I imagine most people will probably adapt very quickly and just be engaging with the end product, or the AI will make up artist personalities for us to engage with in a simulacrum of a real engagement, like a game.

Such a methodical and well-reasoned post! Our relationship to aesthetic experience seems to me a huge issue in the age of AI. Thank you for sharing your insights about agency and the role of art in social relations.