What Daniel Naroditsky’s Untimely Death Reveals About Generational Conflict and the Fragility of Trust

When the old won’t let go

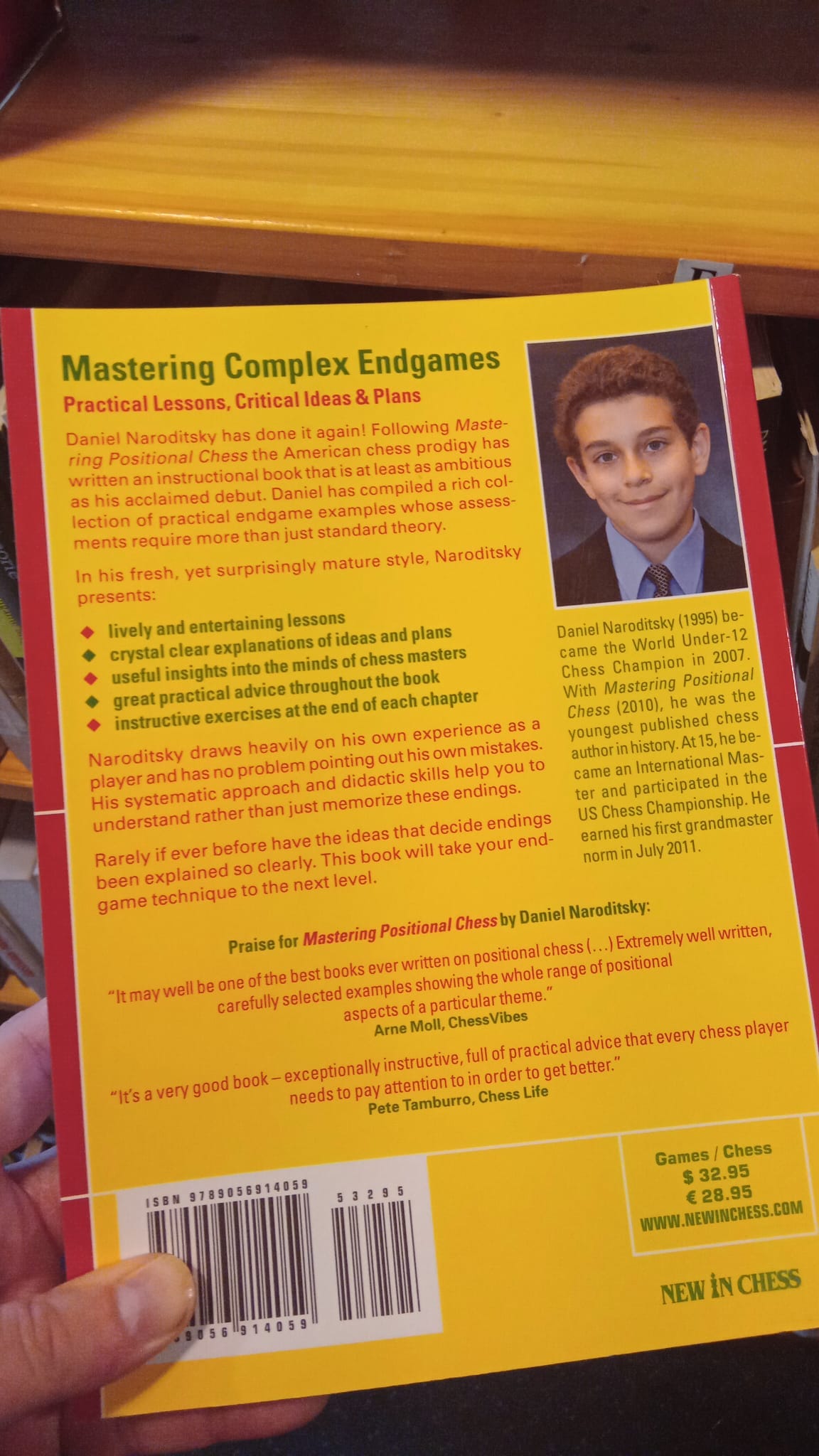

A few years ago, I came across this book in the library section of the Max Euwe Center in Amsterdam. I recognized its author, Daniel "Danya" Naroditsky, whose online chess content I have been following for some time. It seemed impressive that he published his first book so young, only 14. The one I’m holding below was published about two years later.

The news of Naroditsky's untimely passing—at age 29—came as a shock. He was respected not only as a chess player—winning the under-12 World Youth Championship in 2007—but also as an eloquent chess communicator: a writer, teacher, and commentator. I enjoyed many of his streams and educational videos.

Here’s an obituary from the New York Times and BBC.

The cause of death is not yet revealed, or possibly even known, which may or may not be indicative of the cause. Judging from his last stream, Naroditsky still seemed burdened by the cheating allegations initiated by the former world champion, Vladimir Kramnik. This led many people to infer that those allegations, and the surrounding social media drama they caused, had something to do with his death. Here’s from The Guardian:

The world No 2 Hikaru Nakamura delivered an expletive-laden condemnation of Kramnik on his stream, while five-time world champion Magnus Carlsen decried the Russian’s “horrible” conduct. The Indian grandmaster Nihal Sarin, who played Naroditsky in his final online match, accused Kramnik of “taking a life” in remarks to the Indian Express, adding that a relentless campaign of accusations had left his friend “under immense stress”.

Leaving aside the question of what role the cheating allegations may or may not have played in Danya’s untimely death, I want to say a few words about the allegations themselves—and the psychology and sociology behind them.

I’m glad I had the chance to defend Naroditsky against Kramnik’s allegations on X/Twitter while he was still with us. It wasn’t much, but it was more than some others bothered to do (Naroditsky was disappointed that top grandmasters did not publicly voice their support for him).

Cheating allegations are nothing new in chess; they’re part of its long history. What was peculiar in this case was their nature: the relentlessness, coupled with the paucity of evidence, and the apparent absence of good faith behind them. As Naroditsky himself said on one occasion:

I thought he [Kramnik] was going to put out three or four crazy, delusional videos, and then he would move to the next target and eventually the chess world would wake the hell up.

Unfortunately, the opposite happened, and it became apparent to me that this is no longer a case of me being next in line, but a sustained, evil and absolutely unhinged attempt to destroy my life.

Now, top chess players do seem to have a somewhat paranoid and conspiracy-prone mindset. After all, in chess, you have to analyze every move of your opponent and assume it has a function. Everything has a meaning, and everything is interconnected. It is more rational to assume that behind every move there’s an intention and a plan rather than that it is an accident or a coincidence. You assume your opponent is rational and acts in a self-interested way, trying to maximize his winning chances. As you should in chess.

However, when the same mindset is applied outside of chess, it can easily turn into a low-trust outlook and a tendency toward conspiracy thinking. The result can be a proliferation of cheating allegations.

Many of the games we play in everyday life rely on a foundation of trust, chess perhaps being a good example. The proliferation of doubt undermines that trust, revealing just how fragile our social “games” become when the glue that once bound us together begins to loosen and the seeds of mistrust take root.

In Kramnik’s case, I came to the conclusion that his anti-cheating crusade was largely driven by the frustration of an old-world chess champion struggling to adapt to the challenges of the new online era of chess—and to compete with a rising generation of players. Every new defeat, it seemed, was opening a fresh narcissistic wound that had to be cured and rationalized by the assumption that the opponent was—cheating.

It is much easier to accept, psychologically, a defeat from an older, more experienced, and already established competitor than a competitor from your own age. It is even worse when defeated by a junior competitor. In such cases, older competitors can use the status and power they have within the chess community and the public at large to undermine or destroy the reputation of the younger competitor.

The same dynamic extends beyond chess to the social games of everyday life.

There’s a reason sports are divided into age categories: juniors, seniors, and so on. There’s a certain wisdom in this kind of segregation: it doesn’t just make for fairer and more engaging competition, offering us more exciting games to view—it also helps to prevent intergenerational tensions. When players of vastly different ages and life stages are placed in direct competition, the contest can easily turn into something more than a test of skill—it becomes a clash of values, attitudes, and even worldviews.

For example, one generational clash in values and attitudes revolves around the issue of “flagging” your opponent. In chess, “flagging” refers to winning a game by letting your opponent’s clock run out of time, even if your own position on the board is losing or obviously inferior. Flagging is often considered a legitimate and even entertaining part of the game among younger online players—a test of reflexes and time management as much as strategy. Older and/or more traditional players, however, tend to view it as unsporting, a sign of how integrity and respect for the game’s intellectual spirit are being eroded by the culture of instant gratification and streaming entertainment.

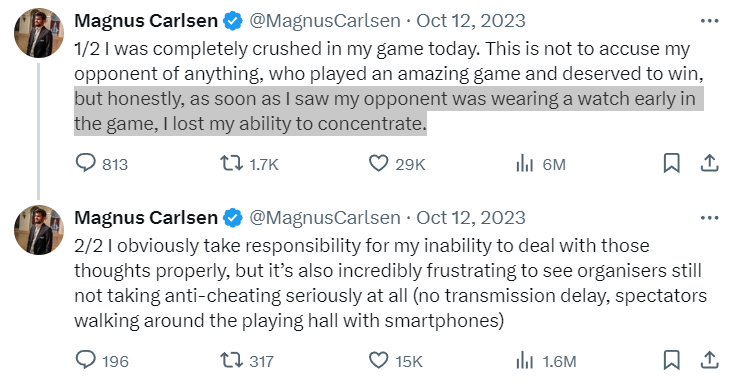

Case in point:

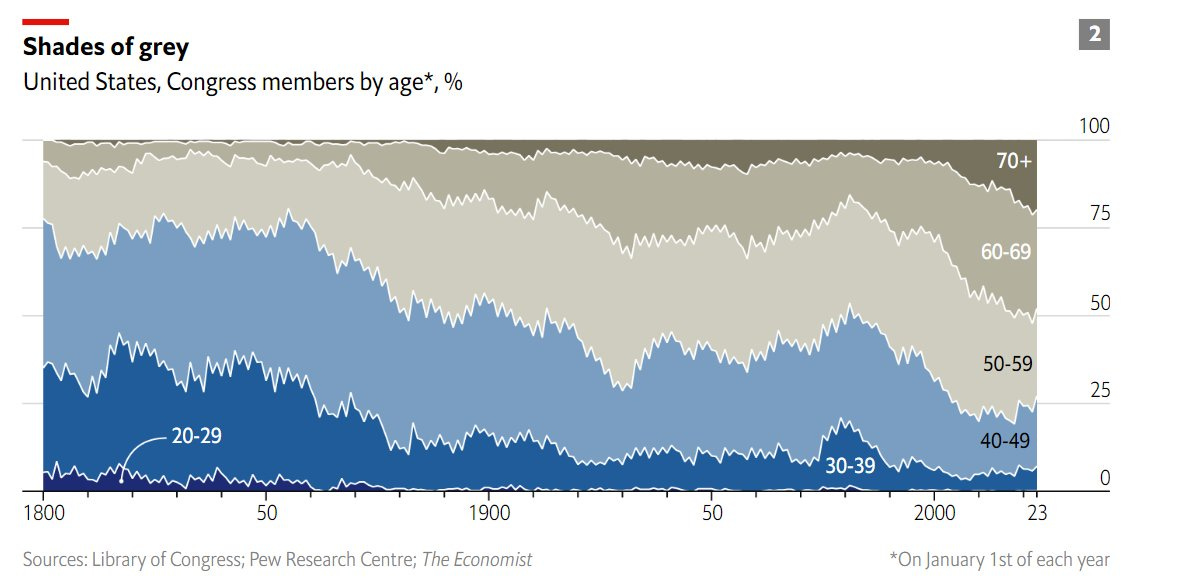

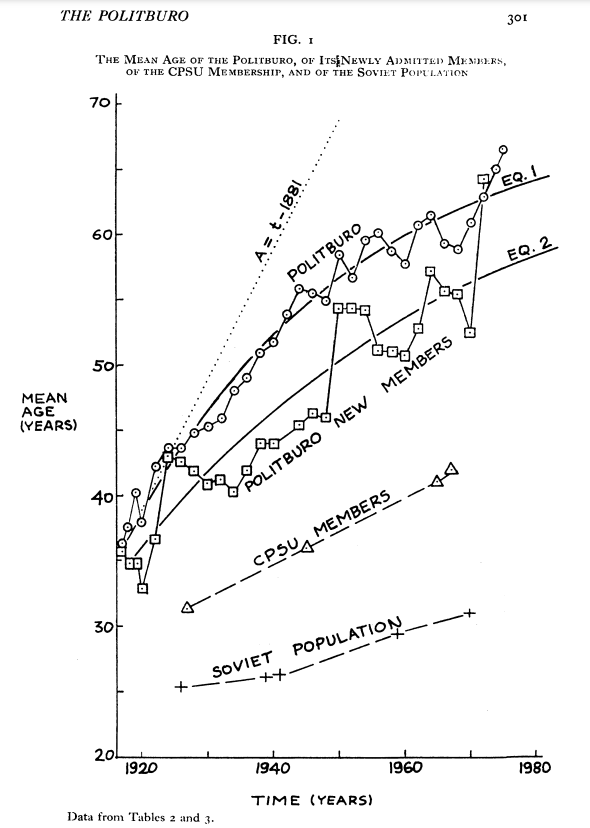

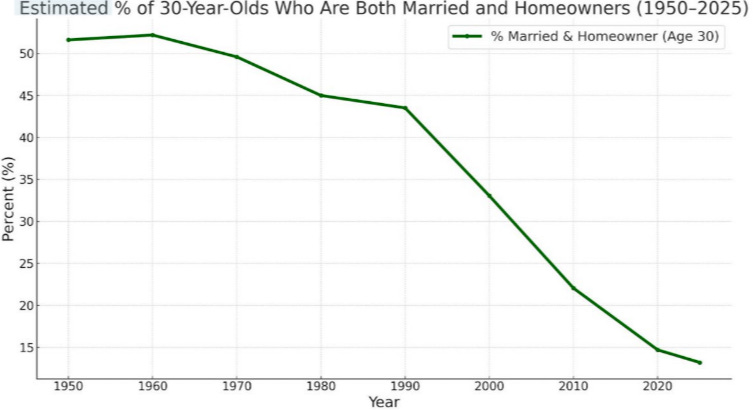

Of course, the old should know when it’s time to “make room” for the young, to quit or retire—but that seems to be happening less and less. In many modern societies, the percentage of older people is steadily growing, with public policies increasingly reflecting their needs and interests. Advances in medicine and technology enable people not only to live longer, but to remain active far beyond what was once typical. They take testosterone replacement therapy to sustain vigor, Viagra to extend their sexual lives, cosmetic procedures to soften the signs of age, and nootropics to preserve mental sharpness. The result is a demographic and cultural landscape where the old no longer quietly step aside but continue competing with the young, consuming resources in spheres once reserved for the young.

Nothing exposes the fakeness of “intergenerational solidarity” rhetoric more than boomers clinging to their institutional posts long past retirement. One may imagine them presiding over national demographic institutes, lamenting declining fertility rates while simultaneously blocking younger successors, displacing them from careers, and pushing them out—out of careers, and sometimes out of the country altogether.

As Peter Thiel noted in his e-mail to Mark Zuckerberg and others:

…in a healthier society, the handover from the Boomers to the younger generations should have started some time ago (maybe as early as the 1990s for Gen X), and that for a whole variety of reasons, this generational transition has been delayed as the Boomers have maintained an iron grip on many US institutions. When the handover finally happens in the 2020s, it will therefore happen more suddenly and perhaps more dramatically than people expect or than such generational transitions have happened in the past. And that’s why it’s especially important for us to think about these issues and try and get ahead of them.

One example of such an “iron grip” from my colleague Eric Weinstein: Of the 67 top research universities in the US, 62 have Baby Boomer presidents (three are Silent Generation and only two are Generation X). Today, the median age of these 67 university presidents is 65 years-old... And this is very different from the recent past. Only thirty years ago, in 1990, the median age of these same university presidents was a much lower 52-years old; the older generation did not completely refuse to give up power; and therefore much greater generational diversity was to be found in university leadership.

Or, to take a small but suggestive example from US Presidential leadership: Three Presidents (Clinton, Bush 43, and Trump) were all born within 70 days of one another, in the summer of 1946. These three people were literally at the head of the Baby Boomer class that was born nine months after World War II ended in September 1945. In my mind, they somehow derived much of their power from the self-referential narcissism of the Boomers as this unusually large cohort of people voted for people like themselves and could afford to ignore anyone younger... and again, this iron grip has been maintained for a shockingly long period of time; but it will not be maintained forever.

Universities and politics are, of course, only a small part of the broader picture—just one of the many arenas where younger generations are being pushed out, especially white and male. Here is, for example, an excerpt from the recent Compact magazine piece on the evaporation of opportunities for young white men among writers:

Over the course of the 2010s, the literary pipeline for white men was effectively shut down. Between 2001 and 2011, six white men won the New York Public Library’s Young Lions prize for debut fiction. Since 2020, not a single white man has even been nominated (of 25 total nominations). The past decade has seen 70 finalists for the Center for Fiction’s First Novel Prize—with again, not a single straight white American millennial man. Of 14 millennial finalists for the National Book Award during that same time period, exactly zero are white men. The Wallace Stegner Fellowship at Stanford, a launching pad for young writers, currently has zero white male fiction and poetry fellows (of 25 fiction fellows since 2020, just one was a white man). Perhaps most astonishingly, not a single white American man born after 1984 has published a work of literary fiction in The New Yorker (at least 24, and probably closer to 30, younger millennials have been published in total).

These are all reasons why some people talk about the need to establish Critical Age Theory as an academic field:

when it comes to age, we see group disparities in favor of the old alongside legal and social institutions set up to officially favor them. If one looks at many of our most serious problems — out-of-control housing costs, a looming debt crisis, rampant credentialism, etc. — the direct distributional consequences of policy choices that society has made are clear enough.

If these structural biases seem abstract, their consequences are not. The latest obsession of the gerontocratic political elites is to drag the European youth to the Ukrainian battlefield. Just imagine being a young man in Ukraine: your government is kidnapping you from the streets to throw you into battle as cannon fodder—all in hopes that your country will one day join the EU, where—in case you survive—you will be replaced in the name of “diversity” and “equality”.

Comically evil.

But now I digress.

Or am I?

I should emphasize, in closing, that I’m not suggesting Daniel Naroditsky was one of those “vanishing” young white males. I have no evidence that his professional opportunities declined after the cheating allegations emerged (although he did express his belief. For now, it appears the primary toll on him was psychological—the relentless burden of having to prove his innocence. What his death does reveal, however, is something broader: the older generation’s difficulty in relinquishing power and trusting the young, and how costly the erosion of trust can be—not only between individuals, but between generations.

Social trust is much like gravity: so fundamental to our way of life that we rarely notice it, even though everything depends on it. Its importance becomes clearest only when it’s gone.