The Uses and Abuses of Victimhood

Victimhood as a coalition-building technology used by low-status groups to gain status

Negative experiences provide a stronger foundation for solidarity than positive ones. They point to a problem or a need, and recognizing the same negative experience in others creates a natural basis for forming a coalition to address that problem or need.

In his Theory of Moral Sentiments, Adam Smith noted the asymmetry in sympathizing and communicating negative compared to positive emotions:

We are still more anxious to communicate to our friends our disagreeable than our agreeable passions, that we derive still more satisfaction from their sympathy with the former than from that with the latter, and that we are still more shocked by the want of.

Coalitional instincts are rarely built around positive experience. Happiness is not indicative of a problem or a need. We rarely empathize with happy people, not only because a happy person is not in a state of need, but also because someone who is not in need is less likely to need us, meaning less likely that social partnership will arise.

Need binds us together. Empathy is a coalition-building tool.

(This is why empathy is always selective and directed toward one group rather than applied universally. Only ingroups are eligible for empathy. When it comes to outgroups, empathy gets substituted with the attribution of bad motives and intentions.)

Suffering, oppression, and trauma become potent platforms for political organizing because victimhood provides brothers-in-arms. Its function is to sustain a sense of threat from the enemy. By keeping the wounds fresh in the memory of its holders, victimhood narratives reinforce group cohesion.

As a coalition-building technology, victimhood is not specific to the political left. This, I think, is to be expected since any group can be inflicted with harm and in need of group cohesion and organizing, thus requiring a moral narrative to mobilize in-groups to be vigilant and seek retribution, a compensation for the wrongdoing imposed on them.

However, even though victimhood is practiced all over the political spectrum, I would assume it is more common in political movements that historically have been considered on the left side of the ideological spectrum; perhaps because care for the weak, poor, or downtrodden is an essential part of what being on the left means.

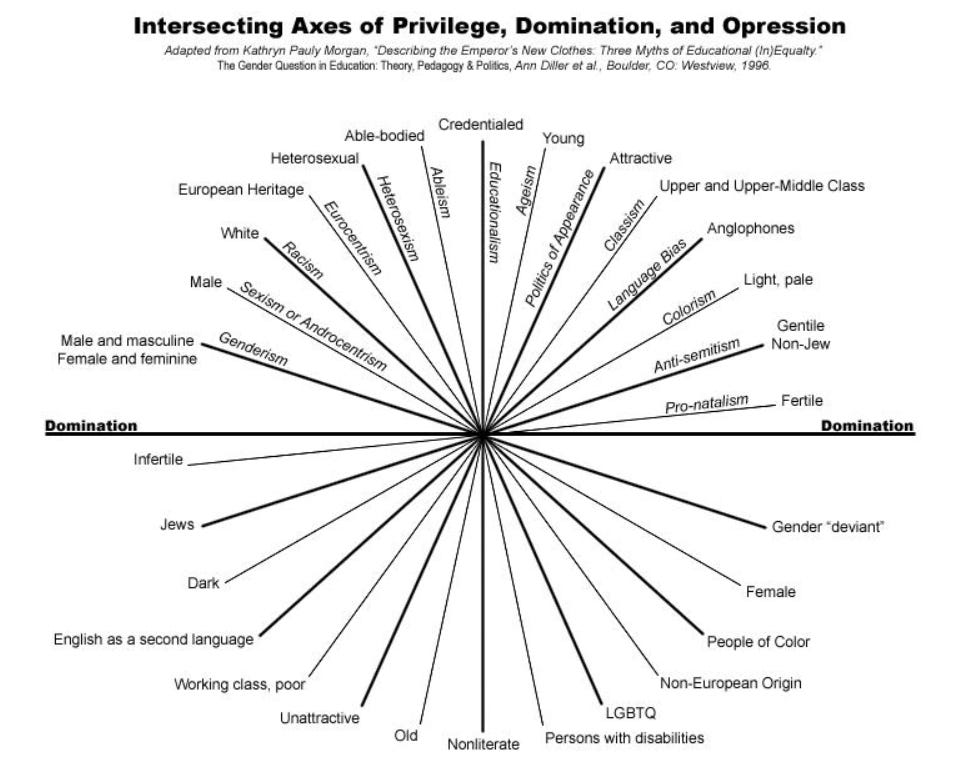

Intersectionality politics (also known as identity politics, or woke politics) is one example of a left-wing movement organized around victimhood and oppression. As I have argued in The Myth of Trauma, the politics of intersectionality could be understood as a coalition-building strategy, one that finds a common denominator between heterogeneous groups in “oppression”.

But this is not an entirely novel or modern phenomenon.

Communist and socialist movements are another historical example. Here we have a promise that the poor, the wretched of the earth, shall rise:

Arise, you prisoners of starvation!

Arise, you wretched of the earth!

For justice thunders condemnation.

A better world's in birth.

No more tradition's chains shall bind us.

Arise, you slaves, no more in thrall!

The earth shall rise on new foundations.

We have been naught, we shall be all.

But whereas communism was primarily concerned with class-based oppression and its emancipation, contemporary intersectionality politics is concerned with all forms of “oppression”—whether based on ethnical/racial, gender, sexual, class, or some other form of an individual’s identity. This enables it to unite a very diverse group of people into a single political platform.

This is why many people call intersectionality politics “Cultural Marxism”—because it seems to generalize the oppression narrative beyond the individual’s economic, class-based, identity, into the “cultural” one.

The great evolutionary biologist Bill Hamilton once observed:

In a sense a dominance hierarchy has only one satisfied individual—she or he at the top. If the hierarchy is bottom-numerous rather than linear, as is the case with most human hierarchies, it is all the more true that the vast majority of people are dissatisfied, wishing they were higher up, a thought which provides a basic reason why democracies (and especially, within democracies, such institutions as their state school systems) have to be unstable. We see a wobbly pyramid, and particularly within that pyramid we see certain side stairs all human examples have by which demagogues skip up a level or two so as to shout down to the restless base that the whole structure is somehow “wrong”. Under a different system, the demagogue shouts, “You could be higher too”.

At any moment, more people will be dissatisfied than satisfied with any given social order. This dissatisfaction creates a need for a narrative that not only makes sense of an individual’s disparate life choices and preferences but also offers an alibi for personal failures and shortcomings. When such a narrative is overly personal and idiosyncratic, it remains an individual’s private story.

However, when it can be generalized and embraced by a larger group, it transforms into a political force—an ideology.

Being a victim may provide a sense of meaning for one’s misfortune, but also foster a feeling of entitlement—the belief that others owe you something. Convincing others that harm has been inflicted on you—and moreover, that others are responsible for that harm—can instill a sense of indebtedness in them. In that sense, somewhat paradoxically, victimhood may be a device for making other people subordinate.

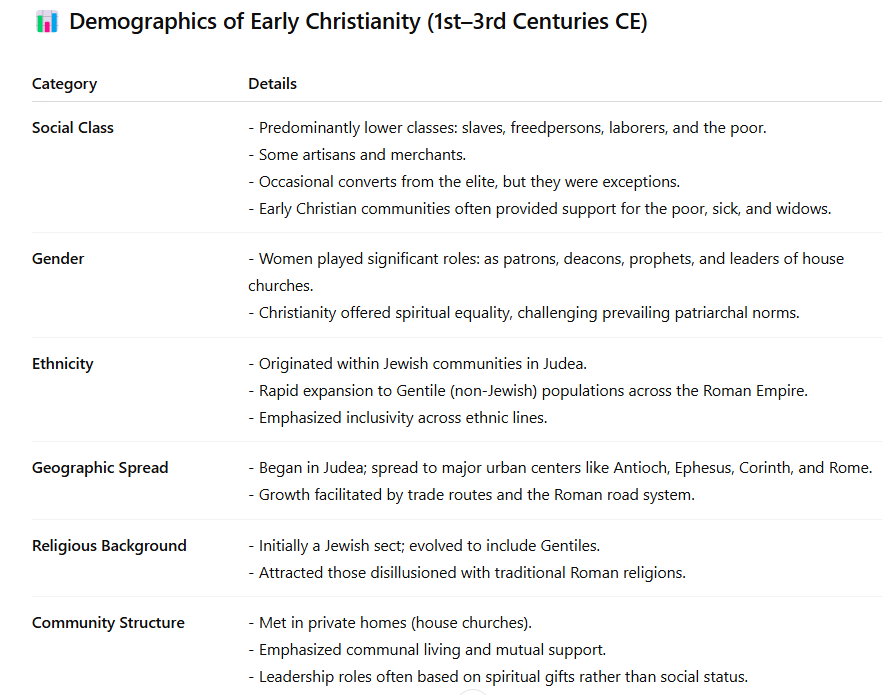

Yet another well-known historical example of a social movement organized around victimhood and oppression would be Christianity, especially in its inception. Here, again, we have the promise that the powerless shall inherit the earth.

As Wikipedia’s article on Christianity’s initial spread mentions:

Christianity appealed to marginalized groups (women, slaves) with its message that "in Christ there is neither Jew nor Greek, neither male nor female, neither slave nor free" (Galatians 3:28).

Nietzsche (in)famously argued that Christianity stems from the resentment the weak feel toward the powerful. It represents the morality of the slaves seeking to overthrow the values (or traits?) of health, strength, beauty, pride, self-confidence, courage, truthfulness, trustworthiness, open-mindedness—the values constituting the morality of the master—with what he saw as life-denying values such as pity, guilt, torture, victimhood and suffering, self-denial, revenge, pettiness, weakness, timidness, ugliness and so on:

Christianity should not be beautified and embellished. It has waged deadly war against this higher type of man; it has placed under a ban all the basic instincts of this type, and out of these instincts it has distilled evil and the Evil One: the strong man as the typically reprehensible man, the "reprobate." Christianity has sided with all that is weak and base, with all failures; it has made an ideal of whatever contradicts the instinct of the strong life to preserve itself. It has corrupted the reason even of those strongest in spirit by teaching men to consider the supreme values of the spirit as something sinful, as something that leads into error — as temptations. The most pitiful example: the corruption of Pascal, who believed in the corruption of his reason through original sin when it had in fact been corrupted only by his Christianity.

Thus spoke Nietzsche in The Antichrist (§4)

The slave morality, therefore, is a reaction to oppression—it villifies the strong and successful because they see them as a cause of their oppression. It is defined through negation.

However, Nietzsche overshoots his target when he accuses Christianity of “the will to nothingness” and “self-destructive instincts,” I think. As Eric Hoffer said, “It is doubtful whether the oppressed ever fight for freedom. They fight for pride and power—power to oppress others.”

Rather than viewing Christianity’s victimhood as a nihilistic force “that wants to bring about the end,” it seems more reasonable to interpret it—at least in its original form—as a kind of coalition-building tool, similar to the way it has been employed by past communist or socialist movements and, more recently, by woke politics. In this light, victimhood is a coalition-building technology most often used by low-status groups or individuals to challenge the existing status hierarchy and reshape the criteria for allocating social status in a way that benefits those initiating the change.

One way to charitably approach Nietzsche’s master–slave morality would be to interpret it as a distinction between a set of preferences and values characteristic of high-status vs low-status groups or individuals.

Most political differences, it could be argued, are generated by a desire to reach power on the one hand and a desire to maintain power on the other hand.

It is easy to confuse the real causes of political differences with the reasons with which each side is attempting to rationalize said desires.

Do social conflicts lie at the level of ideas and arguments, or are the ideas and arguments simply chips with which each side plays the political game?

Take the issue of free speech: is the free speech debate so vigorous because free-speech attitude constitutes an essential part of each political group’s ideology? While both big political parties in the United States have believed, at various points in time, that free speech is one of the values they are deeply committed to in a time-invariant and context-free way, and had good-sounding stories explaining their commitments, the truth is proabably that their attitudes toward free speech were determined by their position relative to power. The Bolshevik revolutionary Nikolai Bukharin expressed perfectly the “strategic inconsistency” of such political values by saying: “We sought freedom of the press, thought, and civil liberties in the past because we were in the opposition and needed these freedoms to win power. Now that we have won, there is no longer any need for such civil liberties”.

The values and preferences that enable an individual or a group to acquire resources or power are often not the same as the values and preferences that enable them to maintain resources and power. Hence the inconsistency.

Those who have the power set the rules of the game, while those who want to reach power seek to redefine the rules in a way that would make them more powerful.

Nietzsche believed that the conflict between master and slave moralities repeatedly resurfaces throughout history and that the language, narratives, practices, and institutions of every culture are shaped by the ongoing tension between these two moral frameworks.

Communists and socialists fought against the market as a procedure that allocates status, power, or privilege to individuals. Contemporary woke critics reject standardized testing, such as SATs and IQ tests, as procedures for college admission and job selection.

Christians, especially early ones, condemned not just any specific procedure or mechanism generating status inequalities but the very idea of worldly success as a measure of value. Since the weak and disenfranchised could not assert power in worldly terms, as part of a broader compensatory mechanism, they created a moral universe where earthly signs of power and success are to a large extent irrelevant—even contemptible—because the true judgment happens after death, in the eyes of God.

Since engines of status distribution and power inequalities vary with time, the details of demand vary with time, but underneath the surface is always a fundamental demand for “equality,” which, more often than not, is really a disguised demand for more power for those who lack it.

Against this interpretation, it could be argued that although people do change some of their values and preferences when they become powerful, master (or slave) morality for Nietzsche is not simply the morality of those who (don’t) have the power, since the strong can lose power and weak may gain it. The weak gain power by joining large groups, by forming political coalitions—their strength arising from their numbers.

What really distinguishes master morality for Nietzsche is that it is a set of values of those strong-willed individuals who were able to exercise power directly, who gained power by virtue of possessing values or traits that are conducive to power, such as strength, health, intelligence, etc.

In a passage echoing Nietzsche’s master-slave morality, Eric Hoffer writes:

It has often been said that power corrupts. But it is perhaps equally important to realize that weakness, too, corrupts. Power corrupts the few, while weakness corrupts the many. Hatred, malice, rudeness, intolerance, and suspicion are the faults of weakness. The resentment of the weak does not spring from any injustice done to them but from their sense of inadequacy and impotence. We cannot win the weak by sharing our wealth with them. They feel our generosity as oppression.

Perhaps one major reason “power corrupts” is that the wrong people so often come to possess it.

The first third seems to be broadly true of fascism as well, hence Umberto Eco describing the "Deceptively Strong/Weak Eternal Opponent" - the ideology that the movement is both strong and victimised. It doesn't have to make sense as long as you can build a coalition out of the abuse of victimhood.

I've never studied Nietzsche, but when he speaks, he gets my attention.